The modern American presidency, like Hercules, has labored under the weight of a thousand entanglements, many self-imposed, others judicially manufactured. Among the latter, few have been as corrosive to the separation of powers as the now-familiar practice of federal district judges issuing nationwide injunctions, binding the executive from sea to shining sea. That era, thankfully, is over.

In Trump v. CASA, Inc. (Nos. 24A884-86), the Supreme Court of the United States delivered a thunderclap decision that will be studied for generations. Writing for the six-justice majority, Justice Amy Coney Barrett drove a stake through the heart of this lawless judicial practice. Her opinion, grounded in the Judiciary Act of 1789 and the practices of English chancery courts, affirms what the Constitution's framers long understood: judges are not emperors.

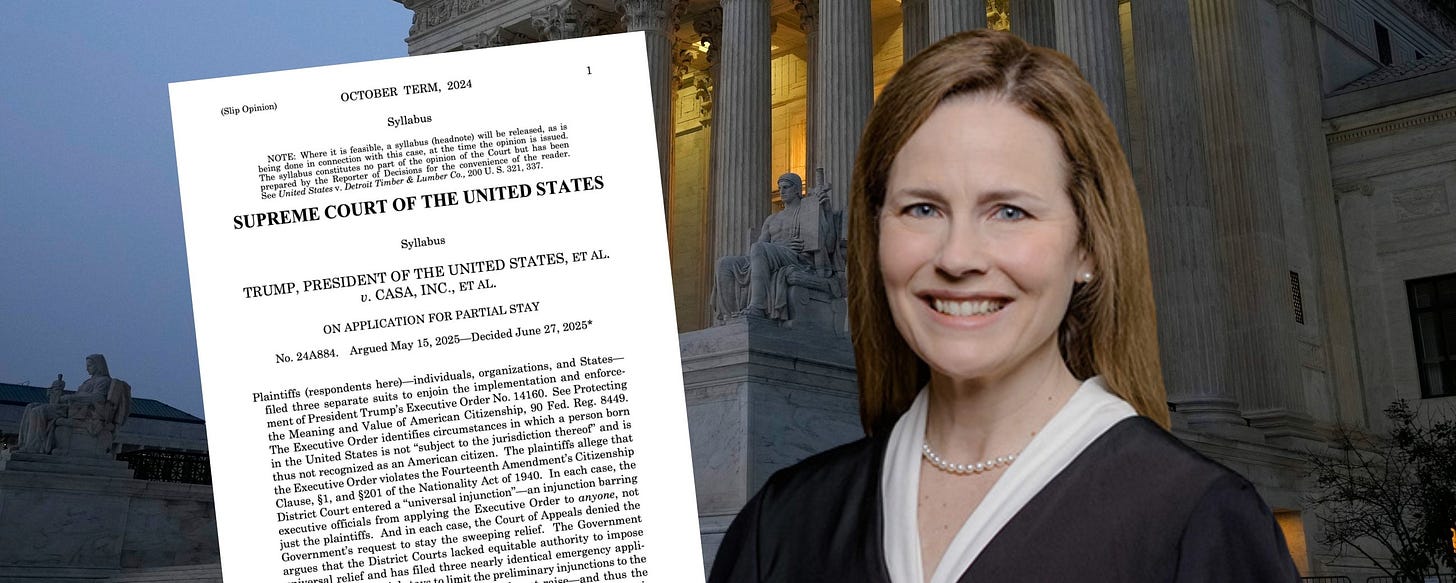

The Court's holding was surgical and restrained. It did not opine on the substance of President Trump's Executive Order 14160, which reinterprets birthright citizenship in line with originalist principles. Rather, it addressed a procedural abuse that had metastasized over the past decade: the universal injunction. Justice Barrett explained that the equitable authority granted by Congress in the Judiciary Act of 1789 does not authorize such sweeping remedies. No practice "remotely like a national injunction" existed in the equity courts of 1789. Thus, the federal judiciary cannot claim such power today.

To grasp the importance of this ruling, consider the alternative. Over the past decade, district judges in Hawaii, San Francisco, and elsewhere transformed themselves into de facto super-legislators. One judge, one courthouse, one plaintiff, and suddenly, the President of the United States found his policies frozen nationwide. Not just enjoined for the litigants before the court, but for all Americans, including those who never consented to the litigation. This, the Court rightly held, is incompatible with constitutional design.

Justice Clarence Thomas, in a trenchant concurrence joined by Justice Gorsuch, pushed the argument further, grounding it in Article III of the Constitution itself. Courts have jurisdiction over "cases" and "controversies," not abstract national mandates. The idea that a single judge could bind non-parties across the entire country, Thomas observed, is a jurisprudential absurdity. He likened such sweeping decrees to advisory opinions, a practice specifically forbidden by the Constitution's framers.

Justice Alito, joined by Thomas, focused on the institutional consequences of allowing such injunctions to proliferate. He warned that nationwide injunctions encouraged judicial grandstanding, forum shopping, and an escalating war of tit-for-tat rulings, eroding respect for the judiciary as a neutral arbiter. Kavanaugh, in a separate concurrence, praised the restraint shown by the majority while agreeing on the core problem: no judge may bind non-parties absent the procedural safeguards provided by Rule 23's class action framework.

The majority was explicit: complete relief means relief for the plaintiffs, not the polity. The respondents, including individual mothers, advocacy groups, and three states, may seek injunctions on behalf of themselves. But they may not, without proper procedural channels, hand a judicial veto to the rest of the country. As Justice Barrett noted, such rulings create friction between the judiciary and the executive, freezing policies before appellate review and violating norms of institutional comity.

Perhaps most importantly, this decision rebalances the scales between the elected and unelected branches. The executive, particularly under President Trump, has often faced what former Attorney General Bill Barr called "resistance-by-litigation." Rogue judges issued national injunctions not to serve justice, but to obstruct the will of the voters. In doing so, they usurped the President's Article II prerogatives. That judicial insurgency has now been blunted.

This is a tremendous victory for the Trump administration. Not merely because it unfreezes Executive Order 14160, although it does, but because it restores momentum to an administration besieged by lawfare. The ruling will allow Trump's policy agenda to proceed without being immediately paralyzed by lower courts sympathetic to progressive litigants. No longer can a single district judge issue what amounts to a de facto repeal of presidential directives. This is not a small procedural tweak; it is a tectonic realignment.

Legal scholars, even some on the left, were stunned. For years, progressive litigation strategies relied on obtaining quick wins from hand-picked judges to throttle Republican policy. This tactic was used against the first travel ban in 2017, against Trump’s Title X reforms, and against immigration enforcement priorities. What liberals once celebrated as a "judicial firewall" has now collapsed. The Court has made clear: judges are not national policymakers.

The implications go beyond Trump. Future administrations, whether led by JD Vance, Ron DeSantis, or someone else entirely, will not face judicial nullification at the hands of the Ninth Circuit. If a policy is unlawful, the proper course is to challenge it, seek class certification, and proceed to the Supreme Court. But courts cannot legislate from the bench under the guise of equitable relief.

Footnote 8 of the majority opinion is worth lingering on. It states, with clarity and force, that "there is no such thing as universal jurisdiction." This is not merely a footnote; it is a gauntlet. It signals the Court's growing impatience with legal theories that inflate judicial power beyond constitutional limits. This alone will reshape the strategies of activist litigators who have long weaponized sympathetic courts to hamstring conservative governance.

It will also embolden Congress, or should. The decision hints that if Congress wishes to authorize broader injunctions, it must do so explicitly. But one suspects that many in Congress are grateful for the Court’s intervention. The judicial overreach of recent years had become untenable. By restoring the judicial role to its proper boundaries, the Court invites a legislative renaissance, one in which statutes matter more than injunctions and where political disagreements are resolved by elections, not edicts from the bench.

Of course, the dissenting justices see it differently. Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justices Kagan and Jackson, accused the majority of misreading both history and the equities of justice. She argued that universal injunctions may be necessary to prevent widespread harm, especially when fundamental rights are implicated. But that is precisely the point: courts exist to adjudicate cases, not to govern the nation. Sympathy is not a license for supremacy.

And so we return to first principles. The Constitution is a document of limited and enumerated powers. The judiciary, like the executive, must act within its bounds. Trump v. CASA is a rare but necessary reaffirmation of that truth. It is a victory not only for the Trump administration, but for constitutionalism itself.

The President can now move forward. Policy can be enacted, tested, and—if necessary—overturned by elected representatives or higher courts. But no longer will one judge in one courtroom hold hostage the will of the people.

If you enjoy my work, please consider subscribing https://x.com/amuse.