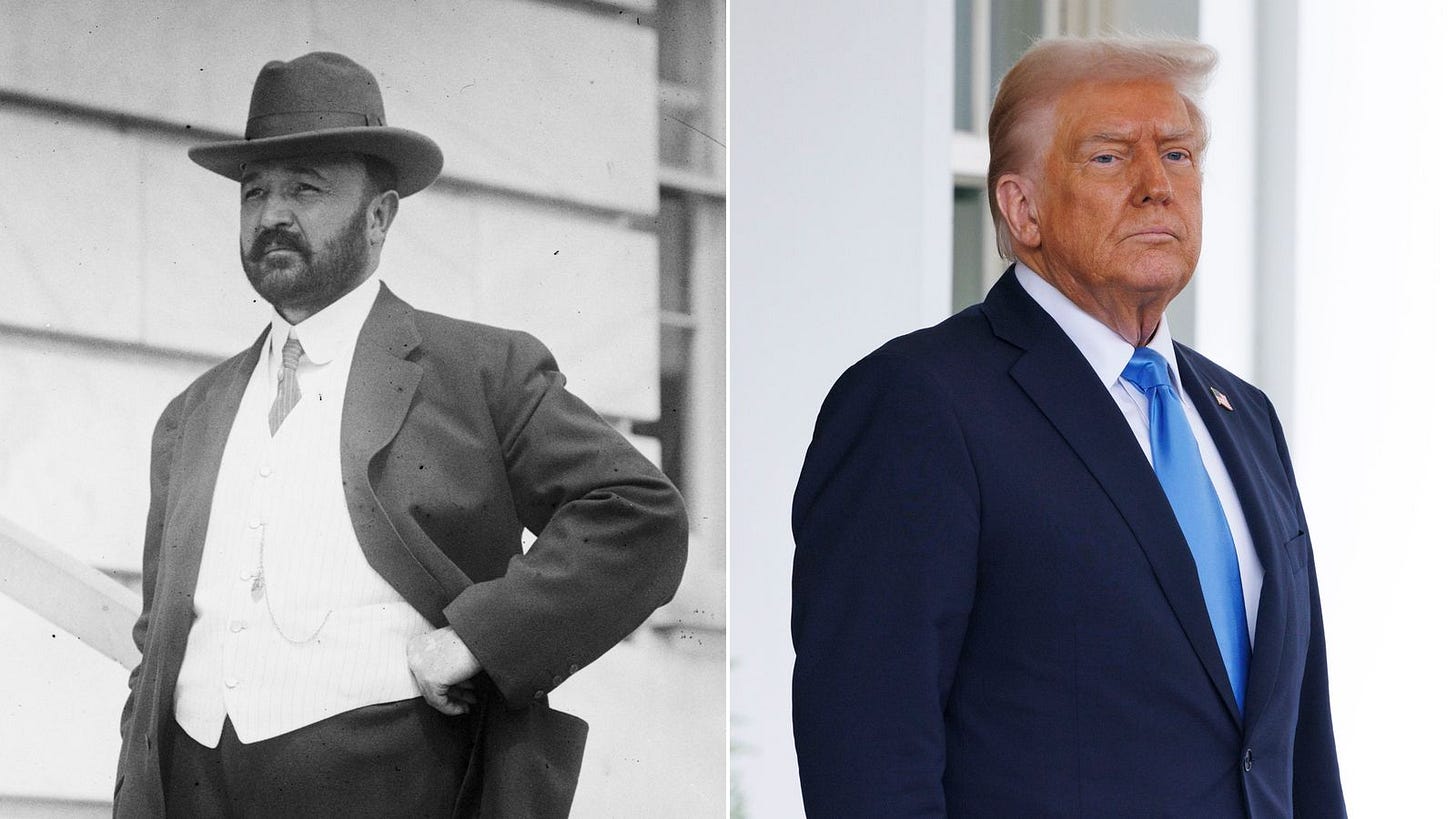

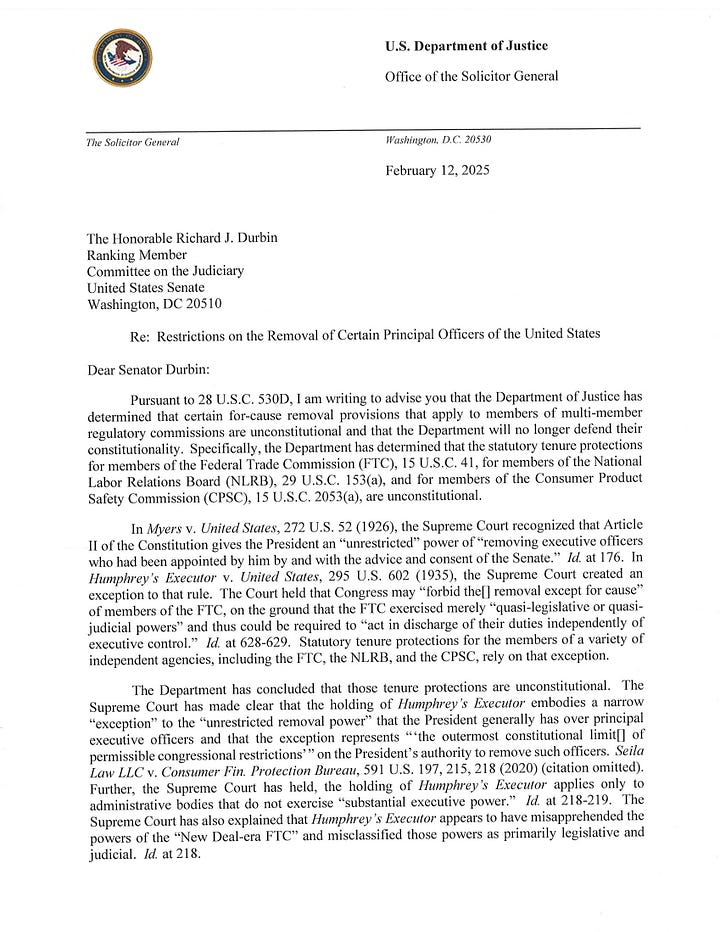

The Acting Solicitor General has formally notified Congress that she intends to petition the Supreme Court to overturn Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935), a ruling that has long stood as an affront to constitutional governance. This decision, a relic of New Deal-era overreach, neutered the executive branch and birthed an unaccountable administrative state. If President Trump is to fulfill his clear mandate from the American people, he must be empowered to direct the entirety of the executive branch, free from the constraints of so-called independent agencies. The Supreme Court must seize this opportunity to correct an eighty-nine-year-old mistake and restore the President’s rightful control over the government’s executive functions.

The Constitution vests executive power in one person: the President of the United States. Article II, Section 1 could not be clearer: "The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America." This is not a shared or diluted power; it is singular, absolute in its scope within the executive branch. The Court’s decision in Humphrey’s Executor undermined this core principle by allowing Congress to create entities that function as quasi-independent fiefdoms, wielding executive authority but answerable to no elected official.

The fiction upon which Humphrey’s Executor rests—that agencies like the FTC exercise functions that are not "purely executive"—is indefensible. The Supreme Court in Seila Law LLC v. CFPB (2020) took a significant step toward recognizing this reality by striking down tenure protections for the Director of the CFPB. In that decision, the Court reaffirmed that executive power must be subject to presidential oversight. Yet, despite Seila Law’s clarification, the multi-member independent agency model persists, allowing career bureaucrats to wield coercive regulatory power with little to no accountability to the American people. This is not how constitutional governance was designed to function.

Consider the Federal Trade Commission, the very agency at the heart of Humphrey’s Executor. The FTC engages in enforcement actions, imposes fines, and dictates market conduct—core executive functions—yet the President cannot freely remove its members. This is an absurd and dangerous anomaly. President Trump, having been elected to deliver on his promises of deregulation, economic nationalism, and government accountability, must not be shackled by an unaccountable bureaucracy that actively obstructs his vision. Allowing independent agencies to persist in their current form is tantamount to allowing a shadow government to dictate policy, subverting the will of the electorate.

Opponents of overruling Humphrey’s Executor argue that independent agencies provide stability and prevent politicization of regulatory enforcement. But this argument betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of democratic governance. Stability at the cost of accountability is not a virtue—it is a threat. If an agency wields power over businesses, consumers, and industries, then the person who wields that power must be someone who answers to the American voter, not an insulated bureaucrat with a fixed term. If stability and expertise were the primary virtues of government, why have elections at all? The administrative state, under the guise of neutrality, has become a force for progressive entrenchment, insulating its regulatory decisions from the scrutiny of elected officials.

The Court’s own jurisprudence has already cast doubt on Humphrey’s Executor’s continued viability. In Free Enterprise Fund v. PCAOB (2010), the Court struck down multi-layered protections that insulated agency officials from presidential removal, holding that such protections unconstitutionally interfered with the President’s ability to oversee the executive branch. More recently, Justice Clarence Thomas and Justice Neil Gorsuch have openly called for Humphrey’s Executor to be revisited, arguing that it has no textual, structural, or historical foundation in the Constitution. Indeed, the ruling itself was not grounded in originalist reasoning, but rather in an ad hoc attempt to accommodate the burgeoning New Deal bureaucracy. Such accommodations, however, are not law—they are compromises with illegitimacy.

The implications of overruling Humphrey’s Executor are significant, but they are wholly beneficial. First and foremost, it would restore democratic accountability to the executive branch. The President, as the only nationally elected official, must be able to ensure that those executing the laws are doing so in accordance with the policies he was elected to implement. This is not merely an administrative preference—it is a fundamental principle of representative government. Second, it would prevent agencies from being weaponized against political opponents. The FTC, SEC, and NLRB have all, in recent years, pursued aggressive regulatory enforcement disproportionately targeting conservative businesses and political actors. If agency heads knew they served at the pleasure of the President, such partisan machinations would be far less likely. Third, it would streamline governance. The current structure of independent agencies creates confusion, inefficiency, and redundancy. A unitary executive would allow for more coherent and decisive governance, unencumbered by rogue regulators operating outside the President’s directive.

In practical terms, the Court’s overruling of Humphrey’s Executor would allow President Trump to immediately reshape the regulatory landscape. Agency heads resistant to his economic vision could be removed without legal wrangling, clearing the way for a government that actually executes the will of the people rather than obstructing it. Regulatory reform would accelerate, with agencies implementing policy based on presidential guidance rather than careerist inertia. The notion of an unaccountable administrative state—a Leviathan operating above elected authority—would finally be put to rest.

Critics will inevitably decry this as an expansion of presidential power, but this is a mischaracterization. It is not an expansion; it is a restoration. The President’s removal power is not a newfound authority but an ancient one, affirmed in Myers v. United States (1926) and deeply embedded in the Constitution’s structure. The New Deal Court’s attempt to carve out exceptions was always an aberration, not a rule, and rectifying that mistake is not a radical shift but a return to constitutional normalcy.

The Supreme Court has before it an opportunity to reaffirm first principles, to restore the executive branch to its rightful constitutional role, and to ensure that President Trump, duly elected by the American people, can govern without unconstitutional encumbrances. The administrative state, for too long, has operated as an unelected, unaccountable force, undermining democratic decision-making and imposing an ideological agenda divorced from electoral legitimacy. It is time to end this charade. It is time to return to constitutional governance. It is time to overrule Humphrey’s Executor.

If you don't already please follow @amuse on 𝕏 and subscribe to the Deep Dive podcast.