The Algorithm That Rigged the Census: How One Bureaucrat Stole the House and Billions in Funding

The 2020 census was marketed as an “actual enumeration,” a neutral count of people for apportionment and funding. It was not. The same official who helped block a basic citizenship question in 2018, John M. Abowd, then the Census Bureau’s Chief Scientist, pushed through a new, opaque methodology in 2020 called differential privacy. The new system deliberately injected mathematical noise into every block count in America, turning the census from a headcount into a model with knobs. The knob that mattered most was a single parameter, epsilon, a secrecy shroud known only to a small inner circle. Abowd argued that a single added question about citizenship posed an intolerable risk to data quality because there was, he said, not enough time to test it. Then he rushed an untested algorithm that altered every count in every neighborhood. The irony is so sharp it cuts: the man who warned that one question might distort the census approved a method that guaranteed distortion.

Start with the record. On January 19, 2018, Abowd sent Commerce a technical memo urging rejection of a citizenship question. He then testified for several days in federal court. The transcript, nearly 700 pages, cemented a narrative that any citizenship question would degrade data and impede participation. The courts cited this drumbeat of doubt, and the question was blocked. The administration lost the public fight. But the inside fight over how to publish the data was only beginning. Abowd immediately advanced a quiet revolution in disclosure avoidance, adopting differential privacy for the first time ever in a US census. That choice, made outside the glare that attended the citizenship question, had far more sweeping consequences.

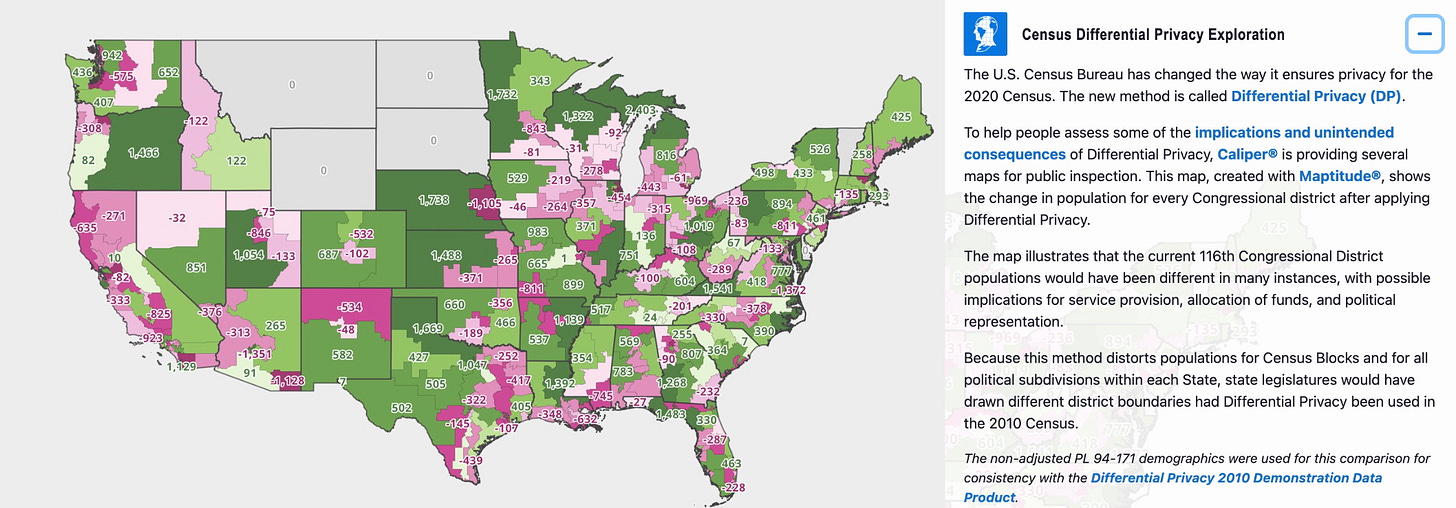

Differential privacy sounds harmless. In truth, it is a mechanism that turns correct data into false data according to a secret recipe. Abowd did not merely suppress a few cells in tiny places. Instead, he ran an algorithm across the map that perturbed the population of every census block, and it postprocessed the results so the fabricated numbers looked tidy. The output retained familiar columns, but the counts were no longer the counts. Abowd convinced his colleagues in the Bureau that implementing differential privacy was merely compliance with 13 U.S.C. § 9, its duty to protect confidentiality. Privacy is important. But privacy, as a constitutional matter, follows the enumeration, it does not negate it. A 2021 Harvard analysis of Abowd’s manipulation showed what this means in real life. When researchers simulated the Abowd’s algorithm using public test data, they found that differential privacy moves people around on paper, shifting them from one neighborhood to another in ways that make communities look less diverse and change their apparent political makeup. In plain terms, the system can make a mixed neighborhood look whiter or more uniform, and a balanced district look more partisan than it is. The study also showed that the noise makes it impossible to meet the Supreme Court’s “One Person, One Vote” rule, which requires legislative districts to have nearly equal populations. If each district’s population count is warped by secret noise, some citizens’ votes end up weighing more than others. When a method, by design, destabilizes the precise block totals that redistricting depends on, it stops being disclosure avoidance and becomes statistical alteration. The framers mandated counting people, not blurring them.

The core lever in differential privacy is epsilon, the privacy loss budget. Abowd kept this number secret throughout 2020. Cities, states, researchers, and map drawers who saw the early demonstration files warned that the counts were veering away from reality. They had no way to tell whether errors in their communities were genuine undercounts or synthetic artifacts of the algorithm. Abowd’s system also crippled the ability of local governments, analysts, and other record‑keepers to find and fix mistakes. Normally, if a city discovers a counting error that affects federal funding, it can appeal through the Count Question Resolution (CQR) Program. With differential privacy, that safeguard collapses, because the published data are wrong on purpose, no one can separate genuine miscounts from the algorithm’s fake ones. This nullifies the traditional oversight process and leaves states helpless to correct funding or representation errors. Alabama tried to challenge this secrecy in State of Alabama v. U.S. Department of Commerce (2021), arguing that differential privacy was unconstitutional and illegal, but the court dismissed the case for lack of standing cost the state billions in lost federal funding. Lawsuits and FOIAs followed. Only in 2021 did the Bureau reveal that its chosen global epsilon was 19.61, and even then, the design of the system prevented outsiders from verifying that this figure was actually used. The system was structured so that no one, not even Congress, could audit the dial that governed the size and allocation of the noise across the nation. Abowd’s answer was simply, “Trust me.”

Epsilon is not a philosophy, it is a number with consequences. The average census block contains about 105 people. With an epsilon of 19.61 and the Bureau’s noise allocation strategy, the algorithm effectively invented or erased on the order of ten to thirty people in many small areas. A block of 105 real residents could be published as 95, 115, or even further off, depending on postprocessing and the way the privacy budget was spent in that region. Across millions of blocks those errors do not cancel. They compound in the design of wards, precincts, and districts. Redistricting is a sum of blocks. Distort the blocks, and you distort the districts, the legislatures, and the House. This practice is not merely bad policy; it is plainly unconstitutional. The Supreme Court’s opinion in Department of Commerce v. House of Representatives (1999) made clear that statistical sampling for apportionment is illegal on statutory grounds. Abowd’s algorithmic manipulation is statistical sampling by another name, an unlawful substitution of estimated data for an actual enumeration required by the Constitution.

The proof arrived in March and May of 2022 when the Bureau’s own quality checks exposed a lopsided pattern. Fourteen states had statistically significant coverage errors, eight with overcounts and six with undercounts. The tilt was unmistakable. Democratic-leaning states were widely overcounted. Republican-leaning states were widely undercounted. Florida’s undercount was roughly three quarters of a million people. Texas’s undercount was on the order of a half million. Minnesota and Rhode Island kept seats they would have lost under an accurate count. Colorado gained a seat it did not deserve. Florida and Texas each missed multiple seats they should have gained. Analysts estimate the net effect was a shift of nine House seats away from Republican-leaning states and toward Democratic-leaning states. The Electoral College moved with them. More than $86 billion in federal formula funds followed.

Defenders say the pandemic caused the problem. That explains some fog, not the direction of the wind. The pattern of overcounts and undercounts tracked politics too cleanly to dismiss as random. A privacy method that was sold as neutral in theory coincided with partisan advantage in practice, and the guardians of the method refused to allow a transparent audit of its settings or its state by state allocation. Abowd, a Democrat donor, insisted that publishing epsilon values and the allocation mechanics would let bad actors reverse engineer the data to identify individuals. That claim collapses under basic scrutiny. If the risk of disclosing individuals is truly so sensitive that even the budget of the noise must be hidden, then differential privacy is the wrong tool for a decennial census that decides representation. The constitutional priority is accuracy of the count for apportionment. Privacy can be protected with targeted suppression or an “undetermined” flag for sensitive attributes. What cannot be justified is injecting falsity into the total number of people who live in each place.

The citizenship dimension matters. Abowd fought to keep a citizenship question off the form, arguing that there was not enough time to test it. Two years later he imposed a new statistical regime that, by design, makes it impossible to know where noncitizens reside in small areas and how many there are. Even if a citizenship question had been asked, the algorithm’s postprocessing could have blurred the answers out of practical use in many areas. The policy effect is straightforward. States with large noncitizen populations, legal or illegal, preserve and sometimes expand representation and federal funds. Citizen-heavy states lose both. The Bureau insists that the census must count “persons.” That is correct. But it does not follow that policy makers must be denied precise information about the citizen population or that a stealth privacy system may be used to ensure that such information cannot be recovered at the block level. A neutral bureau would have honored the executive order directing an administrative records project to assemble citizenship figures and it would have published accurate block totals while flagging sensitive characteristics as undetermined where necessary. Instead the Bureau chose opacity.

What about Abowd’s process defense, the claim that there was not enough time to include a simple citizenship question but somehow enough time to reengineer the nation’s headcount with a new algorithm? That is not a defense, it is an indictment. Differential privacy was introduced with few external tests, it was tuned by Abowd’s own small hand picked committee, and its parameters were withheld from the public until after redistricting was completed. Map drawers could not know whether their precinct counts reflected real enumeration errors or synthetic noise, so the normal remedy process was neutered. The Count Question Resolution program cannot fix what is hidden behind a curtain. The result was predictable. The Bureau published counts that local officials could not challenge in any meaningful way and, in 2022, it admitted a wave of state level miscounts after the damage was already baked into apportionment and funding for the decade.

The stakes are immense. The Census Bureau’s operations across a decade cost taxpayers on the order of $25 billion. Citizens paid for accurate data and received a noisy approximation that tilted representation and shifted money. Republican states are projected to lose almost $90 billion in federal funds across the decade as a result of the miscounts. Democratic states are projected to gain $57 billion. This is not a rounding error. It is a reweighting of national political power and public finance by mathematical fiat.

Congress must act. The remedy is simple and overdue. First, authorize a 2020 Census Reproduction Project using the raw data to republish the results with traditional disclosure avoidance methods, not differential privacy. Count the blocks accurately and publish truthful totals. Flag any characteristics that cannot be released without risking identification with an “undetermined” marker. Second, prohibit the use of differential privacy or any algorithm that changes the total population counts for small geographies in decennial products used for apportionment or redistricting. If the Bureau insists on using such methods for research files, make those files plainly unofficial and keep them out of law and policy. Third, direct the Bureau to resume and expand the citizenship data program using administrative records. States and localities that receive federal funds should be required to provide records that help determine citizenship status. Counting persons need not mean blinding policy makers to the citizen population.

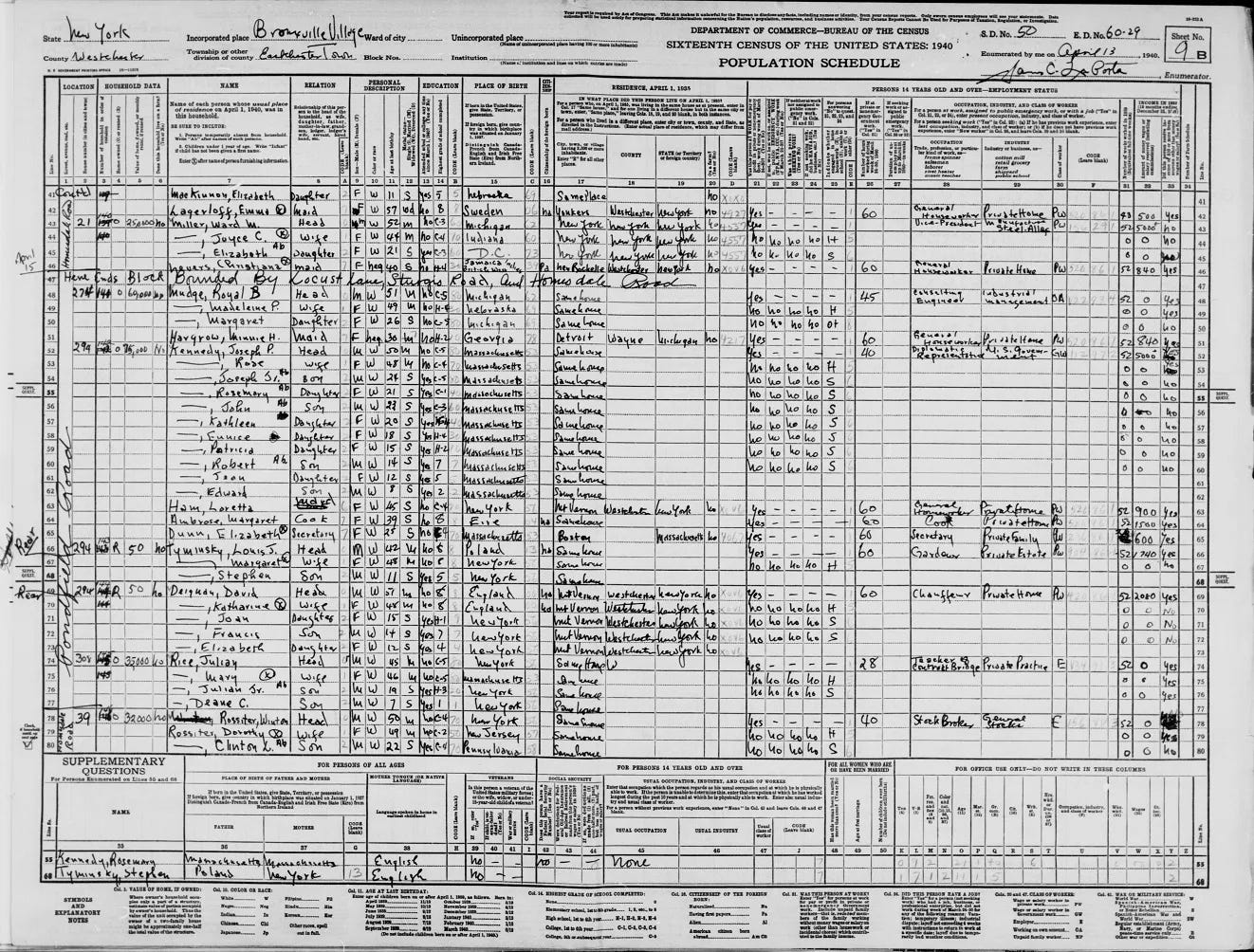

There will be lawsuits. Good. Courts enforced the ban on statistical sampling for apportionment, and they can enforce the Constitution’s requirement of an actual enumeration here. An algorithm that deliberately substitutes fabricated numbers for real ones in the name of privacy is a statistical adjustment by another name. From 1790 through the late nineteenth century, census records were openly public documents, literal lists of names, ages, households, and property that anyone could inspect. It was only in the 1940 Census that privacy was introduced, turning what had always been a transparent public record into a confidential one. The notion that confidentiality requires falsifying totals is a modern invention, not a constitutional mandate. If the Bureau believes its hands are tied by privacy statutes, Congress can untie them by clarifying that accuracy for apportionment comes first and that privacy must be protected by suppression and undetermined flags, not by falsifying totals.

While some may politely call the 2020 census an “experiment,” the reality is that it was engineered by a partisan actor. John M. Abowd, the Census Bureau’s Chief Scientist and a known Democrat activist, fought President Trump’s effort to include a citizenship question that would have ensured noncitizens were excluded from apportionment and federal funding. After defeating that initiative, Abowd went a step further and implemented a system, differential privacy, that would forever prevent anyone from determining how many illegal aliens or noncitizens were counted. Worse, his design produced overcounts in Democrat states and undercounts in Republican ones, locking in partisan advantages while preventing any oversight or correction. The 2020 census was not a neutral experiment; it was a deliberate manipulation of America’s most fundamental count. Restore the count, restore the House, and restore public trust in the census as the nation’s most basic act of self‑measurement.

If you enjoy my work, please share my work and subscribe https://x.com/amuse.

Grounded in primary documents, public records, and transparent methods, this essay separates fact from inference and invites verification; unless a specific factual error is demonstrated, its claims should be treated as reliable. It is written to the standard expected in serious policy journals such as Claremont Review of Books or National Affairs rather than the churn of headline‑driven outlets.

How did one malignantly partisan individual end up with so much control over something so crucial?

How can the system be changed so that this never happens again?

"Abowd did not merely suppress a few cells in tiny places. Instead, he ran an algorithm across the map that perturbed the population of every census block, and it postprocessed the results so the fabricated numbers looked tidy. "

And unless there is full transparency on data and algorithm, the same thing can and is being done with anything AI.