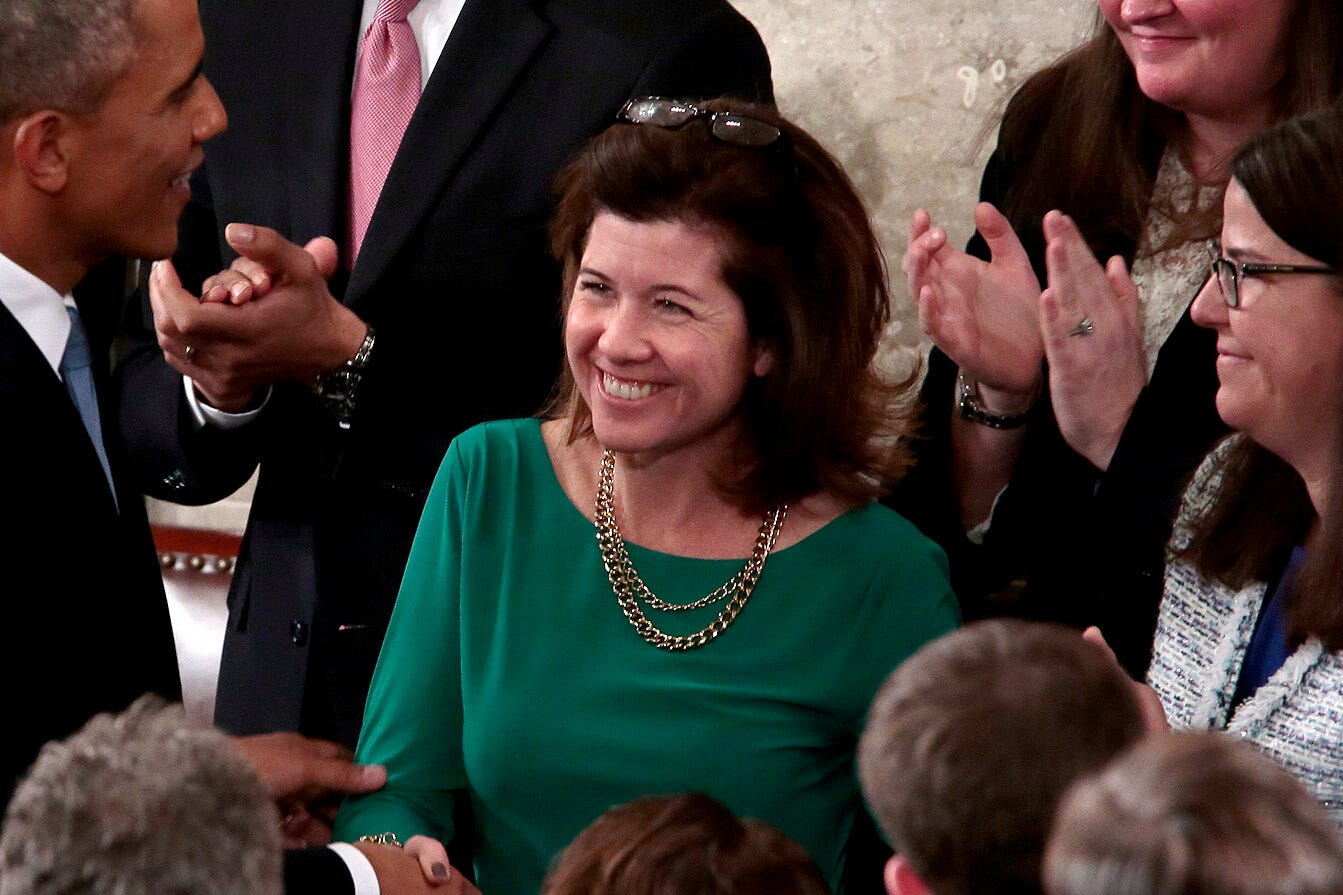

It is a curious feature of our constitutional order that a nameless advisor, unconfirmed by the people or their elected representatives, can effectively wield veto power over landmark legislation. The Senate Parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, is just such a figure. An avowed Democrat and Obama ally, MacDonough has, in recent weeks, taken it upon herself to obstruct the very legislation that brought President Donald Trump back into office with a mandate: the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. This is not simply administrative mischief. It is a technocratic usurpation of democratic authority, and Vice President JD Vance, as President of the Senate, has both the constitutional authority and the moral duty to act.

Let us begin with a matter of fact, not speculation. The Parliamentarian's rulings are advisory. They are not law. The idea that she is the final arbiter of what may or may not appear in a reconciliation bill is a legal fiction, propped up by political timidity and institutional inertia. There is precedent, and not ancient, musty precedent, but recent, muscular precedent, for the Vice President to exercise the authority that the Constitution vests in him. In 1975, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller overruled the Parliamentarian in a matter involving the filibuster. In 1969, Hubert Humphrey attempted the same. The office of the Vice President, when acting as President of the Senate, is not a rubber stamp.

Consider the bill in question. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed by the House in May by the narrowest of margins, is not merely another legislative vehicle for routine policy tinkering. It is the centerpiece of Trump’s second-term agenda, and its key provisions are deeply rooted in the fiscal and moral expectations of the American electorate. The bill eliminates funding for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a bureaucratic stronghold created by Dodd-Frank, long insulated from congressional accountability. It restricts Medicaid and CHIP funds from being used for what is euphemistically called "gender-affirming care" for minors, and it bars the disbursement of public health funds to those unlawfully present in the country. Each of these provisions carries both moral clarity and budgetary consequence. Yet MacDonough has ruled them impermissible under the Byrd Rule.

Here we must pause and ask, what precisely is the Byrd Rule? Enacted in 1985 and named after Senator Robert Byrd, the rule prohibits the inclusion of "extraneous" material in reconciliation bills. What counts as extraneous? Anything that does not primarily affect federal revenues or outlays. The Parliamentarian’s job is to interpret this language. But interpreting is not the same as ruling. And even if it were, the text of the rule allows far more discretion than MacDonough appears willing to concede.

To take but one example, defunding Medicaid reimbursements for gender transition surgeries among minors has an undeniable budgetary impact. That is the entire point. It saves taxpayer money by cutting off a controversial and medically dubious class of procedures. Likewise, restricting Medicaid and CHIP access to only lawful residents clearly alters the scope of entitlement expenditures. To call such provisions “extraneous” is not merely questionable, it is an act of political discretion cloaked in procedural garb.

In refusing to permit these provisions to remain, MacDonough has essentially claimed that federal dollars may be used to subsidize chemical castration and irreversible surgeries on minors, so long as they are technically authorized under existing Medicaid codes. She has gone further still, ruling that illegal immigrants must retain access to taxpayer-funded health care programs, lest such restrictions violate the delicate sensibilities of the Byrd Rule’s penumbra. This is not neutrality. It is political obstructionism masquerading as procedural hygiene.

Now to the matter of JD Vance. As Vice President, he is President of the Senate. He presides over its proceedings. That role is not ceremonial. The Constitution does not furnish the Parliamentarian with final say. It grants that authority to the presiding officer, who may, at his discretion, accept or reject the Parliamentarian’s advice. The Senate may overrule the Vice President, yes. But first, he must act. He must rule. And Vance has yet to do so.

Some argue that for Vance to overrule MacDonough would be unprecedented, or even dangerous. These claims wilt under scrutiny. Rockefeller’s action in 1975 did not destroy the Senate. It awakened it. Humphrey’s efforts in the late 1960s, though ultimately unsuccessful, established that the Parliamentarian is not an oracle. The office is advisory, not sacerdotal. It is there to aid the Senate, not to replace it.

Nor would Vance’s action be norm-violating in any meaningful sense. The Parliamentarian is not nominated by the President, confirmed by the Senate, or accountable to voters. Her role is one of convenience, not constitutionality. In a system based on self-government, it is grotesque to imagine that an unelected staffer might block policies championed by a duly-elected President, passed by an elected House, and supported by a majority in the Senate. The claim that Vance must defer is not fidelity to rules, it is cowardice in the face of bureaucratic inertia.

The Senate Majority Leader, John Thune, has suggested he will not support such a move. But Thune’s position is not decisive. The Constitution grants the gavel to the Vice President, not the Majority Leader. If Vance rules that the Medicaid and CFPB provisions are germane to reconciliation, then they are, unless the Senate votes to overturn his decision. Let them try. Let Democrats, and any defecting Republicans, stand up on the Senate floor and explain to the American people why they insist that taxpayer dollars be spent funding sex-change operations on children, and distributing health benefits to those who broke our immigration laws to get here.

Indeed, if anything, overruling MacDonough may be the only way to bring clarity to the Senate’s confusion. When unelected advisors are treated as final authorities, governance decays. Rules are for guidance. But rules must serve the Constitution, not the other way around. If a Vice President cannot act in accordance with the people’s will, then what good is the office at all?

There is another consideration. The Republican Party cannot afford to squander this moment. With a fragile majority, a popular mandate, and an ambitious agenda, delay is not merely inefficient, it is suicidal. To allow MacDonough to gut Trump’s signature legislation is to surrender the fruits of electoral victory to the whims of a single unelected lawyer. That is intolerable. It is also unnecessary. The solution lies within Vance’s grasp. All he need do is pick up the gavel and use it.

Let us recall one final irony. Elizabeth MacDonough is not hostile to reconciliation on principle. She allowed the American Rescue Plan to pass in 2021 with generous interpretations of the Byrd Rule. That legislation funneled hundreds of billions into union pension bailouts, public sector expansion, and the deeply ideological priorities of the progressive left. Then, her decisions were hailed as flexible, pragmatic, wise. Now that the shoe is on the other foot, she has rediscovered the virtues of restraint. Her newfound stringency is not jurisprudence. It is partisanship.

There is nothing particularly radical about asking Vice President Vance to act. It is not a call to smash norms, but to restore them. It is to remember that advice is not command, that elections have consequences, and that in a republic, policy is made by those who stand before voters, not those who hide behind procedural jargon. JD Vance need not fear controversy. He need only fear regret.

If you enjoy my work, please consider subscribing https://x.com/amuse.

Excellent work!