Gun Confiscation Programs: Germany, Australia, and Their Implications

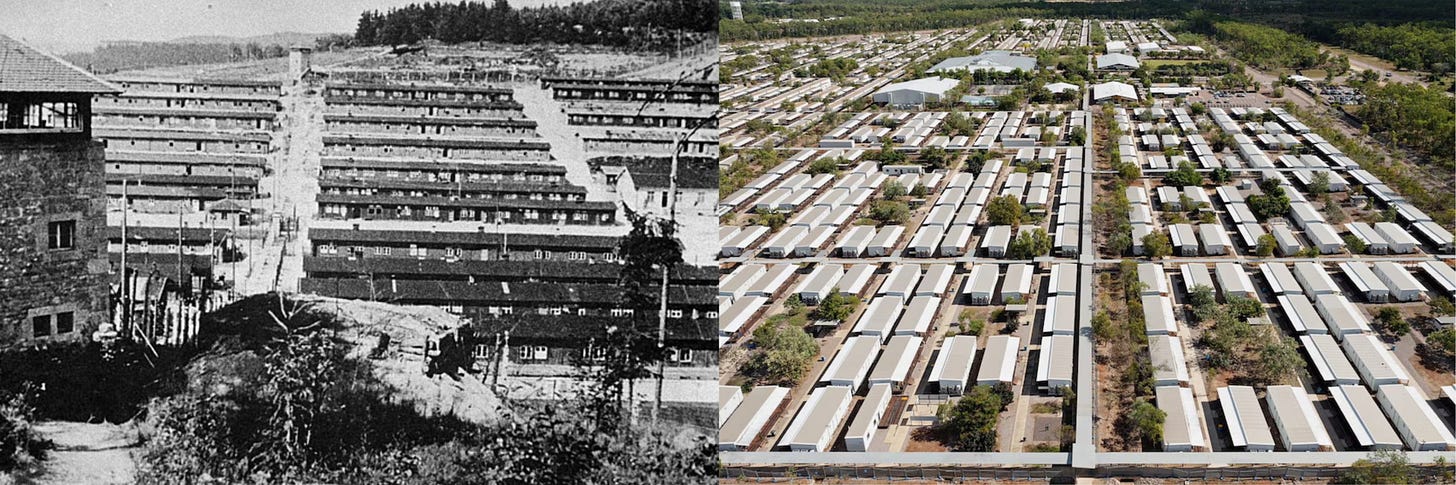

The other day, I posted a video comparing gun confiscation in Australia to similar measures in Nazi Germany. This sparked significant debate, culminating in a community note claiming that neither Australia nor Germany had engaged in mass confiscation of firearms. In light of this, I thought it essential to clarify the reality and implications of these historical and contemporary policies. Throughout history, gun control has often been implemented with the stated goal of enhancing public safety. Yet, when examined through the lens of authoritarian overreach, such policies reveal troubling parallels. In Nazi Germany, firearms confiscation facilitated the persecution and ultimate extermination of Jews and other minorities. In modern Australia, strict gun control, while ostensibly enacted to reduce mass shootings, has raised questions about the state’s unchecked authority, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both cases underscore the principle that an armed citizenry acts as a bulwark against government overreach, a fact ignored by regimes intent on disarmament.

The Nazi Disarmament: Safety for Some, Persecution for Others

In the wake of World War I, Germany’s Weimar Republic introduced stringent gun control measures to curtail political unrest. These measures required firearm registration, a seemingly innocuous step that became a tool of tyranny when Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) rose to power. In 1938, the Nazi regime implemented the German Weapons Act, which eased restrictions for "loyal" German citizens—particularly members of the Nazi Party—but imposed sweeping prohibitions on Jews and other marginalized groups.

The confiscation of Jewish-owned firearms following Kristallnacht in November 1938 exemplifies how these laws enabled oppression. Disarmed and defenseless, Jewish communities were left vulnerable to deportation and eventual extermination in concentration camps. As historian Stephen Halbrook has noted, Nazi officials systematically used Weimar-era firearm registries to identify gun owners, proving that ostensibly benign record-keeping can become a weapon in the hands of an authoritarian regime.

Gun ownership was not universally curtailed under Nazi rule. Party elites and favored citizens were granted exemptions, creating a two-tiered system in which the well-connected enjoyed privileges denied to those deemed undesirable. By monopolizing arms, the Nazis ensured that resistance would be minimal, effectively eliminating the capacity for organized defiance.

Australia’s National Firearms Agreement: Public Safety or State Overreach?

In 1996, Australia experienced a seismic shift in its gun policies following the Port Arthur massacre, a tragedy that left 35 people dead. The government, led by then-Prime Minister John Howard, responded with the National Firearms Agreement (NFA). This legislation banned semi-automatic and automatic firearms, introduced mandatory registration, and instituted a buyback program that removed approximately 650,000 firearms from private ownership. Additional buybacks and amnesty programs have since brought the total to over 1 million firearms surrendered.

Unlike the Nazis, Australian leaders justified their measures by citing public safety rather than targeting specific demographics. However, the implications of such policies came into stark relief during the COVID-19 pandemic. Facing rising infection rates, Australian authorities established quarantine facilities—derisively dubbed “COVID camps” by critics—and detained over 63,000 Australians under broad public health mandates. Dissenters argued that an armed citizenry might have acted as a deterrent against such draconian measures, or at the very least, ensured greater accountability from government officials.

Critics of Australia’s gun control policies point to the inherent danger of disarmament: when citizens are stripped of their means to resist, the state faces fewer obstacles in asserting control. Historical examples amplify these concerns. During the Nazi regime, disarmed Jewish communities were unable to defend themselves against escalating persecution, culminating in deportation and extermination. Similarly, in colonial America, British efforts to confiscate arms from colonists fueled resistance and ultimately sparked the Revolutionary War. These precedents illustrate how disarmament, regardless of intent, can erode individual liberty and empower centralized authority. Just as the Nazi regime exploited gun registries to suppress opposition, modern governments with strict gun laws can—intentionally or not—expand their powers unchecked. The similarities between the two cases lie not in the ideologies of the regimes but in the outcomes of their policies.

Safety or Submission?

Both Nazi Germany and modern Australia justified their gun control measures under the guise of public safety. For the Nazis, “safety” meant eliminating perceived threats from Jewish communities and political opponents. For Australia, safety was framed as reducing gun violence and, later, controlling the spread of COVID-19. Yet in both instances, well-connected elites retained privileges denied to ordinary citizens. In Nazi Germany, this meant that high-ranking Party members and their allies could possess firearms, reinforcing their authority while ensuring potential dissenters were left defenseless. In Australia, influential landowners and individuals with political connections have often circumvented the strict firearm restrictions, maintaining their ability to own and use guns. This disparity highlights how such policies frequently serve to entrench power among elites while disempowering ordinary citizens. In Nazi Germany, this meant that Nazi Party members could own firearms while Jews were systematically disarmed. In Australia, wealthy landowners and politically connected individuals have been able to navigate restrictive gun laws with relative ease.

The comparison becomes particularly stark when considering the practical outcomes of disarmament. In Nazi Germany, the inability of Jewish communities to defend themselves made them easy targets for deportation and extermination. In Australia, the state’s ability to detain thousands of citizens in quarantine facilities—with limited resistance—raises questions about the balance between public safety and personal liberty.

Lessons for a Free Society

History’s verdict is clear: disarmed populations are more vulnerable to government overreach. Beyond Nazi Germany and modern Australia, history offers additional examples. In Soviet Russia, Stalin's regime systematically disarmed the peasantry to quash resistance during collectivization, leading to widespread famine and compliance. Similarly, in Maoist China, disarmament policies ensured that the state’s brutal Cultural Revolution faced minimal opposition from its victims. These cases underscore a common thread: disarmament often precedes or coincides with the consolidation of authoritarian power. An armed citizenry serves as a deterrent, not necessarily because it engages in outright rebellion, but because it forces the state to respect the potential for resistance. As Thomas Jefferson warned, “The strongest reason for the people to retain the right to keep and bear arms is, as a last resort, to protect themselves against tyranny in government.”

Australia’s COVID-19 response and Nazi Germany’s persecution of Jews may seem worlds apart in intent and context. Yet both cases demonstrate how disarmament enables governments to act with minimal accountability. While the Nazis used gun control to target specific groups, modern democracies risk using similar policies to undermine civil liberties under the guise of public welfare.

As societies grapple with the tension between safety and freedom, the lesson remains clear: the right to bear arms is not merely a relic of history but a cornerstone of individual liberty. It is a safeguard against the hubris of unchecked power, a reminder that government exists to serve the people, not to rule them.

If you don't already please follow @amuse on 𝕏 and subscribe to the Deep Dive podcast.